|

Pat Gelsinger is one of the most important tech executives at the world’s biggest chip company and may even head it some day. How he came to be in this position is a story of determination, faith and one very smart mind.

In 1979, Intel recruiter Ron Smith was on his 12th interview of the day when a 17-year-old from Pennsylvania Dutch farm country named Patrick Gelsinger took a seat for his turn at getting a job with this still-unknown California firm.

Smith’s note on the teenager was pretty straightforward: “Smart, arrogant, aggressive — he’ll fit right in.”

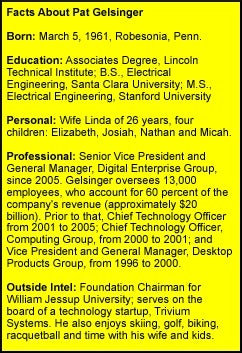

Gelsinger had flown across the country for the interview, even though he had promised his mother he wouldn’t take a job on the west coast. He ended up taking the job for two reasons: First, Intel was willing to pay for his education. If he worked a minimum of 30 hours per week and maintained a B average, his tuition was covered. This enabled him to get his Bachelor’s degree from Santa Clara University and Master’s degree from nearby Stanford University, both in electrical engineering.

But perhaps more than that perk, Intel really pursued him. “Our hiring manager was super aggressive in recruiting me, calling my mom, telling her he’d look after me, make sure I don’t fall in the ocean or get lost in a cult, all the things that east coasters imagine of the west coast,” Gelsinger joked.

Twenty-nine years later, not only has he fit in, Gelsinger has been as significant a presence within the company as Andy Grove and Gordon Moore. As an engineer, project leader, business unit leader, chief technology officer and now senior vice president and general manager of the chip giant’s largest division, the digital enterprise group, he has led some of the most successful product developments in the company’s history. He also oversaw some flops, and actually, didn’t fit in all that well at first — a reminder that it’s how executives overcome adversity that often foretell their future successes.

“There’s a handful of guys at Intel who have been associated with most of the key product programs, and Gelsinger is definitely in that crowd,” said Nathan Brookwood, a long-time analyst in the semiconductor market and research fellow with Insight64.

“What you see with Pat is a deep understanding of the technical side, a deep understanding of the business side, and in general he’s been in the middle of a lot of good decisions Intel has made,” adds Martin Reynolds, a vice president with Gartner. “When you’ve got that kind of combination of business and technical expertise, you have the ability to steer the company down the right course.”

Gelsinger describes Intel as “a very successful culture, if I could call it that, a combination of paranoia from Grove’s environment and pride in our accomplishment, literally, that the things we do change the world. Paranoia in that if we don’t do it faster than the guy next to us, our lunch is going to get eaten.”

Next page: Involved in many projects

Page 2 of 4

Involved in major projects

As an engineer, Gelsinger played a key role in the computer revolution and the arrival of the digital era all throughout the 1980s. He was involved in the development of the 80286 processor (introduced in 1982) and was the fourth engineer on the 32-bit 80386 project (introduced in 1985), and led the 80486 processor’s development from “soup to nuts.”

He got that job after first handing in his resignation.

Gelsinger wanted to finish his masters and get his Ph.D. in electrical engineering at Stanford, to keep at least one promise to his mother. So in 1987, having given his notice of his resignation, Andy Grove, then president of the company, paid him a visit.

“Grove comes to me and says, ‘So the deal is this: you can either learn in the simulator or you can stay here and fly the real jet,’ and he offered me the job as design manager of the 486,” Gelsinger said. “Here I am, 25 years old, being offered one of the crème de la crème assignments of the Valley. I think that might entice me to stay.”

The 386 project proved quite an adventure as well, according to Brookwood. Many of the senior engineers were switched to a new processor design, the IAPX432, that was supposed to take over the world. That left junior engineers like Gelsinger to work on the 286 and 386.

“Gelsinger was working on lifeboat architecture while the rest were working on the new ocean liner,” Brookwood said.

But the IAXP432 ocean liner hit an iceberg. It barely made it out of the labs and never went anywhere and is now a trivia item.

Meanwhile, the young hotshots down the hall figured out how to extend the x86 architecture to 32-bits while preserving backward compatibility, which lead to the 386.

“That’s what put Gelsinger on the map at Intel. It was almost by accident,” Brookwood said.

Life changes

Not everything he touched turned to gold. After the 486 project, Gelsinger went to work on Intel’s ProShare line of video conferencing products. But the technology infrastructure of the late 1980s simply wasn’t ready for it. While it failed, Gelsinger learned from that, too.

|

“ProShare was my biggest failure,” he said. “I learned a ton about myself and how to deal with situations that aren’t going well. Also I learned about how to build teams and peer relationships.”

Another lesson: don’t rely on a new technology that isn’t established in the marketplace. ProShare needed ISDN

Reynolds thinks its unfair to pin the ProShare blame on Gelsinger. “The product wasn’t going to succeed but he managed to move it,” Reynolds said. “There’s a measure of determination there you can regard as valuable, even if the product wasn’t going to succeed.”

“ProShare was part of Pat’s training in the business, and he demonstrated he had what it takes to push a product. Will they make him VP of sales? Probably not.”

Next Page: Inspiration

Page 3 of 4

Inspiration

Although Intel’s recruiter thought Gelsinger’s youthful, brash confidence would fit right in at Intel, the new recruit struggled at first. The move away from Robesonia, Pennsylvania, a tiny town of 2,000 people in Pennsylvania Dutch country to the Silicon Valley was a bit jarring.

His motivation was spurred on when he met the woman who, in 1982, would become his wife, Linda. Linda was a devout Christian and inspired this faith in Gelsinger, who said he’d been raised in a “church environment” but never really religious home. Linda and Patrick had four children, and even though he was a success at Intel, earning a promotion every year he was with the company, Gelsinger found raising a family in the Silicon Valley to be too much personal and financial strain.

He tried to transfer within Intel but got nowhere. Finally, in 1990, he went to Intel President Craig Barrett and informed him of his decision to leave the company.

“I said ‘Craig, here’s the deal: I tried to transfer here, nothing’s working. I want to let you know I’m going to start interviewing outside of Intel because we’ve decided we’re moving out of the Bay Area.’ Craig said, ‘Give me 60 days.’ Forty-five days later, we were in Oregon.”

Gelsinger is still in Beaverton, a wooded Portland suburb not too unlike the one he left behind in the Valley, but less expensive and less congested. He works in nearby Hillsboro, which has become known as “The Silicon Forest” due to the large number of tech firms there, and Intel’s presence is one of the largest, with 16,000 employees in the town.

His star continued to rise at Intel despite being outside of the main headquarters and the failure of ProShare. In 1992, he took over the desktop product group, where he was responsible for all desktop CPUs, chipsets and motherboards. In the late 1990s, Gelsinger came up with the idea for the Intel Developer Forum, a twice-a-year show for hardware and software developers to get the latest news on what Intel has cooking.

The show was meant to counter Microsoft’s Windows Hardware Engineering Conference (WinHEC), which was more about Windows than hardware. It started small, hosted in out of the way locations like Palm Springs in the late 1990s. It then moved to the San Jose Convention Center and finally the Moscone Center in downtown San Francisco, the Mecca of all tech trade shows.

In 2001, Intel made him chief technology officer, the first time a company full of executives qualified to wear the CTO title actually had one. “We had people like Grove and Moore who are pillars in the industry but we never had the official title. I don’t know if it was in vogue or if Barrett was anxious to get me another job, but Craig decided Intel really should formalize this,” Gelsinger said.

Around this time, Craig Kinnie, who was instrumental in getting Intel’s labs in place and leading the PCI and USB projects, retired from the company. “We had labs that were scattered all over the place and he was playing that role but without any title. So Craig decided to pull those pieces together. I was finishing an assignment and he decided to offer it to me,” said Gelsinger.

His mother’s response when he told her the news? “She said ‘that’s great, when are you going to finish your Ph.D.’?” he laughed.

Finding balance

Despite all of this, there were still moments of doubt that crept into his mind, and it led to an internal journey of dealing with the demands of working in a pressure cooker like Intel and being a father to four children, not to mention his position as an Elder with his church in Hillsboro, where he had numerous outside involvements, charitable works, and such.

Once again, things got away from Gelsinger. Work occupied more and more of his time, to the point his wife confronted him with the accusation that his kids began to think of him as a stranger.

“That led me to a period of reevaluation. To chisel these principals around balancing [in stone], I spoke internally a couple of times at Intel as well as externally. A lot of people said ‘wow, you got a lot to say on the subject, you should write a book’,” Gelsinger said.

At first, he put it off until he got to a point where he would try to write it, and practice what he preached about balancing home and work life. That meant not telling his wife about the project. “If I can write about balancing, I can do it without her knowing it. So I did it on plane trips, late nights and so on. When I told her I was writing it and I had a first draft, I was expecting praise. Of course she reacted the exact opposite of what I was expecting. ‘How dare you be writing a book without telling me?'” he laughed.

“Balancing Family, Faith and Work” came out in 2003 and is still popular among Christian organizations. It’s even available in China. Gelsinger isn’t one to proselytize, but he does appreciate Intel’s willingness to support faith groups. Many firms prefer to punt on the subject of faith-based groups and avoid the potential headache by simply not allowing any, but Intel is fairly open to all groups.

“Intel as a company is seen as reasonably progressive on the subject as other companies avoid any support group like that,” said Gelsinger. “Intel has a well-defined policy to support every support group in that regard as long as they fit in certain criteria.” So the company has everything from a Christian group, of which Gelsinger is a part, to Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender employee groups, a Muslim employees group, a Jewish employees group and more.

Gelsinger speaks on work life effectiveness. “Intel has a very strong policy on work-life effectiveness, how we support families, mothers, new mothers, and trying to balance those things in my own life has made me an advocate for those programs within the company,” he said.

Next Page: Head of the ship

Page 4 of 4

Head of the ship

Within Intel and with his church, Gelsinger is involved in a number of charities and works with universities, churches, and missionaries, in both Oregon and around the world. He also serves as Foundation Chair for William Jessup University, a private Christian university in Rocklin, California.

So where does someone who changed the course of chip development at Intel, started its major developer show, and was its first CTO go from here? Up.

“I’ve had as my personal mission statement for many years that I’d like a shot at running the company,” he said. “Of course, that job is well taken now. My goal is to get good enough in terms of my personal capabilities to be considered for that. If not, that’s OK, but still, it’s a driving force to make myself better.”

Brookwood believes Sean Maloney, executive vice president and chief sales and marketing office of the company, is next in line for the top spot after Otellini rides off into the sunset, whenever that is. Intel CEOs have to retire at 65 and Otellini is 57, so assuming everything goes well, he will be around a while.

If Maloney does get the nod, Brookwood suspects the next in line will be one of three people: Gelsinger, David “Dadi” Perlmutter, executive vice president and general manager of the mobility group, or Anand Chandrasekher, senior vice president and general manager of the ultramobility group. All three will be keynote speakers at IDF, starting on Aug. 19, with Gelsinger getting the main address on the first day.

“As I look around Intel at various folks who could move into those slots, clearly Gelsinger could do it,” Brookwood said. “Intel has the luxury of several people who could do it. They groom folks for this, and clearly Pat’s moved around enough in the organization to be able to handle it.”

But he adds the resume is not spotless. Gelsinger signed the deal with Rambus in the late 1990s that proved a boondoggle for Intel, costing it chipset sales and possibly CPU sales as buyers went instead with AMD and the lower-cost DDR memory. Even then-CEO Craig Barrett told The Financial Times in 2001 the deal was “a mistake.”

“Intel’s whole position and the way it approached Rambus was not a good model for how to do it,” Brookwood said. “Boy, did they give Rambus a lot of deals in that contract. Now whether he negotiated or not, I don’t know, but I always thought that was one of the most lopsided deals I’ve ever seen.”

Reynolds said that at the time, Rambus looked like the only reasonable solution. “Memory controllers were getting too big and too slow. Now no one knew Rambus would go sour like it did, either,” he said. Rambus started to up the royalty rates and make it expensive to make Rambus memory, and thus PC prices went up, hurting everyone.

Brookwood thinks Gelsinger needs more non-technological experience. “The one thing I don’t know about Pat is just how conversant he is across all the major, functional areas of the company,” Brookwood said. “If you look at Intel’s typical senior executive grooming practice, people move into the field organization, factory organization as well as development. I don’t think Pat has all of those boxes punched on his game card here.”

On the plus side, Brookwood said Gelsinger is one of the best public speakers at Intel. “Barrett was never very good in that role. Otellini does it OK, but sweats buckets. Pat is very calm and can hit really high notes. Some of his IDF keynotes were just inspiring in some ways,” he said.

Reynolds said Gelsinger has time. “Give it ten years and let’s look again. He needs more seasoning. Running sales and marketing probably wouldn’t be a bad thing to do. If he succeeds at that, then you have a CEO with a near perfect balance of skills. It gives you the respect of all the organizations and the ability to understand all the pieces,” he said.

At 47, Gelsinger still has plenty of time to go. Retirement is not on his mind. “I don’t know that I quite ever see myself retiring because I’m motivated, driven and excited about different aspects of technology. I expect I might graduate to a university at some point,” he said.

Maybe he’ll even get that Ph.D.